from IPython.display import Image

Image('../../Python_probability_statistics_machine_learning_2E.png',width=200)

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(123456)

The absence of the probability density for the raw data means that we have to argue about sequences of random variables in a structured way. From basic calculus, recall the following convergence notation,

$$ x_n \rightarrow x_o $$for the real number sequence $x_n$. This means that for any given $\epsilon>0$, no matter how small, we can exhibit a $m$ such that for any $n>m$, we have

$$ \vert x_n-x_o \vert < \epsilon $$Intuitively, this means that once we get past $m$ in the sequence, we get as to within $\epsilon$ of $x_o$. This means that nothing surprising happens in the sequence on the long march to infinity, which gives a sense of uniformity to the convergence process. When we argue about convergence for statistics, we want to same look-and-feel as we have here, but because we are now talking about random variables, we need other concepts. There are two moving parts for random variables. Recall from our probability chapter that random variables are really functions that map sets into the real line: $X:\Omega \mapsto \mathbb{R}$. Thus, one part is the behavior of the subsets of $\Omega$ in terms of convergence. The other part is how the sequences of real values of the random variable behave in convergence.

¶

Almost Sure Convergence

The most straightforward extension into statistics of this convergence concept is almost sure convergence, which is also known as convergence with probability one,

$$ \begin{equation} \mathbb{P}\lbrace \textnormal{for each } \epsilon>0 \textnormal{ there is } n_\epsilon>0 \textnormal{ such that for all } n>n_\epsilon, \: \vert X_n-X \vert < \epsilon \rbrace = 1 \label{eq:asconv} \tag{1} \end{equation} $$Note the similarity to the prior notion of convergence for real numbers. When this happens, we write this as $X_n \overset{as}{\to} X$. In this context, almost sure convergence means that if we take any particular $\omega\in\Omega$ and then look at the sequence of real numbers that are produced by each of the random variables,

$$ (X_1(\omega),X_2(\omega),X_3(\omega),\ldots,X_n(\omega)) $$then this sequence is just a real-valued sequence in the sense of our convergence on the real line and converges in the same way. If we collect all of the $\omega$ for which this is true and the measure of that collection equals one, then we have almost sure convergence of the random variable. Notice how the convergence idea applies to both sides of the random variable: the (domain) $\Omega$ side and the (co- domain) real-valued side.

An equivalent and more compact way of writing this is the following,

$$ \mathbb{P}\left(\omega\in\Omega \colon\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} X_n(\omega)=X(\omega) \right)=1 $$Example. To get some feel for the mechanics of this kind of convergence consider the following sequence of uniformly distributed random variables on the unit interval, $X_n \sim \mathcal{U}[0,1]$. Now, consider taking the maximum of the set of $n$ such variables as the following,

$$ X_{(n)} = \max \lbrace X_1,\ldots,X_n \rbrace $$In other words, we scan through a list of $n$ uniformly distributed random variables and pick out the maximum over the set. Intuitively, we should expect that $X_{(n)}$ should somehow converge to one. Let's see if we can make this happen almost surely. We want to exhibit $m$ so that the following is true,

$$ \mathbb{P}(\vert 1 - X_{(n)} \vert) < \epsilon \textnormal{ when } n>m $$Because $X_{(n)}<1$, we can simplify this as the following,

$$ 1-\mathbb{P}(X_{(n)}<\epsilon)=1-(1-\epsilon)^m \underset{m\rightarrow\infty}{\longrightarrow} 1 $$Thus, this sequence converges almost surely. We can work this example out in Python using Scipy to make it concrete with the following code,

from scipy import stats

u=stats.uniform()

xn = lambda i: u.rvs(i).max()

xn(5)

0.966717838482003

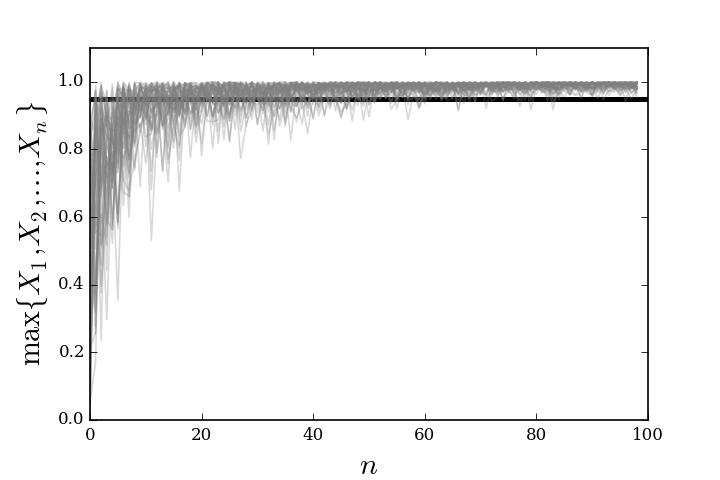

Thus, the xn variable is the same as the $X_{(n)}$ random variable

in our

example. Figure shows a plot of these random

variables

for different values of $n$ and multiple realizations of each random

variable

(multiple gray lines). The dark horizontal line is at the 0.95

level. For this

example, suppose we are interested in the convergence of the

random variable to

within 0.05 of one so we are interested in the region

between one and 0.95.

Thus, in our Equation 1, $\epsilon=0.05$.

Now, we have to find

$n_\epsilon$ to get the almost sure convergence. From

Figure, as soon as we get past $n>60$, we can see that

all the realizations start to fit in the region above the 0.95 horizontal

line. However, there are still some cases where a particular realization will

skip below this line. To get the probability guarantee of the definition

satisfied, we have to make sure that for whatever $n_\epsilon$ we settle on,

the

probability of this kind of noncompliant behavior should be extremely

small,

say, less than 1%. Now, we can compute the following to estimate this

probability for $n=60$ over 1000 realizations,

import numpy as np

np.mean([xn(60) > 0.95 for i in range(1000)])

0.961

So, the probability of having a noncompliant case beyond $n>60$ is

pretty good,

but not still what we are after (0.99). We can solve for the $m$

in our

analytic proof of convergence by plugging in our factors for $\epsilon$

and our

desired probability constraint,

print (np.log(1-.99)/np.log(.95))

89.78113496070968

Now, rounding this up and re-visiting the same estimate as above,

import numpy as np

np.mean([xn(90) > 0.95 for i in range(1000)])

0.995

which is the result we were looking for. The important thing to

understand from

this example is that we had to choose convergence criteria for

both the values

of the random variable (0.95) and for the probability of

achieving that level

(0.99) in order to compute the $m$. Informally

speaking, almost sure

convergence means that not only will any particular $X_n$

be close to $X$ for

large $n$, but whole sequence of values will remain close

to $X$ with high

probability.

Almost sure convergence example for multiple realizations of the limiting sequence.

Convergence¶

in Probability

A weaker kind of convergence is convergence in probability which means the following:

$$ \mathbb{P}(\mid X_n -X\mid > \epsilon) \rightarrow 0 $$as $n \rightarrow \infty$ for each $\epsilon > 0$.

This is notationally shown as $X_n \overset{P}{\to} X$. For example, let's consider the following sequence of random variables where $X_n = 1/2^n$ with probability $p_n$ and where $X_n=c$ with probability $1-p_n$. Then, we have $X_n \overset{P}{\to} 0$ as $p_n \rightarrow 1$. This is allowable under this notion of convergence because a diminishing amount of non-converging behavior (namely, when $X_n=c$) is possible. Note that we have said nothing about how $p_n \rightarrow 1$. Example. To get some sense of the mechanics of this kind of convergence, let $\lbrace X_1,X_2,X_3,\ldots \rbrace$ be the indicators of the corresponding intervals,

$$ (0,1],(0,\tfrac{1}{2}],(\tfrac{1}{2},1],(0,\tfrac{1}{3}],(\tfrac{1}{3},\tfrac{2}{3}],(\tfrac{2}{3},1] $$In other words, just keep splitting the unit interval into equal chunks and enumerate those chunks with $X_i$. Because each $X_i$ is an indicator function, it takes only two values: zero and one. For example, for $X_2=1$ if $0<x \le 1/2$ and zero otherwise. Note that $x \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1)$. This means that $P(X_2=1)=1/2$. Now, we want to compute the sequence of $P(X_n>\epsilon)$ for each $n$ for some $\epsilon\in (0,1)$. For $X_1$, we have $P(X_1>\epsilon)=1$ because we already chose $\epsilon$ in the interval covered by $X_1$. For $X_2$, we have $P(X_2>\epsilon)=1/2$, for $X_3$, we have $P(X_3>\epsilon)=1/3$, and so on. This produces the following sequence: $(1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\ldots)$. The limit of the sequence is zero so that $X_n \overset{P}{\to} 0$. However, for every $x\in (0,1)$, the sequence of function values of $X_n(x)$ consists of infinitely many zeros and ones (remember that indicator functions can evaluate to either zero or one). Thus, the set of $x$ for which the sequence $X_n(x)$ converges is empty because the sequence bounces between zero and one. This means that almost sure convergence fails here even though we have convergence in probability. The key distinction is that convergence in probability considers the convergence of a sequence of probabilities whereas almost sure convergence is concerned about the sequence of values of the random variables over sets of events that fill out the underlying probability space entirely (i.e., with probability one).

This is a good example so let's see if we can make it concrete with some Python. The following is a function to compute the different subintervals,

make_interval= lambda n: np.array(list(zip(range(n+1),

range(1,n+1))))/n

Now, we can use this function to create a Numpy array of intervals, as in the example,

intervals= np.vstack([make_interval(i) for i in range(1,5)])

print (intervals)

[[0. 1. ] [0. 0.5 ] [0.5 1. ] [0. 0.33333333] [0.33333333 0.66666667] [0.66666667 1. ] [0. 0.25 ] [0.25 0.5 ] [0.5 0.75 ] [0.75 1. ]]

The following function computes the bit string in our example, $\lbrace X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_n \rbrace$,

bits= lambda u:((intervals[:,0] < u) & (u<=intervals[:,1])).astype(int)

bits(u.rvs())

array([1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1])

Now that we have the individual bit strings, to show convergence we want to show that the probability of each entry goes to a limit. For example, using ten realizations,

print (np.vstack([bits(u.rvs()) for i in range(10)]))

[[1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0] [1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0] [1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0] [1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0] [1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0] [1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0] [1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0] [1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0] [1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0] [1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0]]

We want the limiting probability of a one in each column to convert to a limit. We can estimate this over 1000 realizations using the following code,

np.vstack([bits(u.rvs()) for i in range(1000)]).mean(axis=0)

array([1. , 0.493, 0.507, 0.325, 0.34 , 0.335, 0.253, 0.24 , 0.248,

0.259])

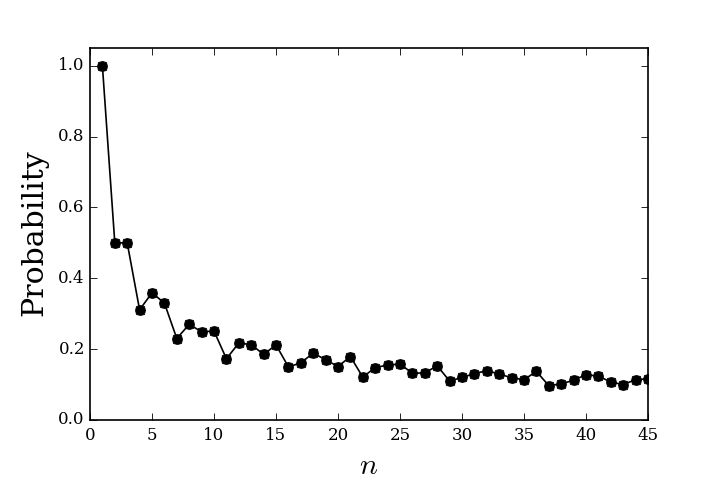

Note that these entries should approach the $(1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\ldots)$ sequence we found earlier. Figure shows the convergence of these probabilities for a large number of intervals. Eventually, the probability shown on this graph will decrease to zero with large enough $n$. Again, note that the individual sequences of zeros and ones do not converge, but the probabilities of these sequences converge. This is the key difference between almost sure convergence and convergence in probability. Thus, convergence in probability does not imply almost sure convergence. Conversely, almost sure convergence does imply convergence in probability.

Convergence in probability for the random variable sequence.

The following notation should help emphasize the difference between almost sure convergence and convergence in probability, respectively,

$$ \begin{align*} P\left(\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} \vert X_n-X\vert < \epsilon\right)&=1 \textnormal{(almost sure convergence)} \\\ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} P(\vert X_n-X\vert < \epsilon)&=1 \textnormal{(convergence in probability)} \end{align*} $$Convergence in Distribution¶

So far, we have been discussing convergence in terms of sequences of probabilities or sequences of values taken by the random variable. By contrast, the next major kind of convergence is convergence in distribution where

$$ \lim_{n \to \infty} F_n(t) = F(t) $$for all $t$ for which $F$ is continuous and $F$ is the cumulative density function. For this case, convergence is only concerned with the cumulative density function, written as $X_n \overset{d}{\to} X$.

Example. To develop some intuition about this kind of convergence, consider a sequence of $X_n$ Bernoulli random variables. Furthermore, suppose these are all really just the same random variable $X$. Trivially, $X_n \overset{d}{\to} X$. Now, suppose we define $Y=1-X$, which means that $Y$ has the same distribution as $X$. Thus, $X_n \overset{d}{\to} Y$. By contrast, because $\vert X_n - Y\vert=1$ for all $n$, we can never have almost sure convergence or convergence in probability. Thus, convergence in distribution is the weakest of the three forms of convergence in the sense that it is implied by the other two, but implies neither of the two.

As another striking example, we could have $Y_n \overset{d}{\to} Z$ where $Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)$, but we could also have $Y_n \overset{d}{\to} -Z$. That is, $Y_n$ could converge in distribution to either $Z$ or $-Z$. This may seem ambiguous, but this kind of convergence is practically very useful because it allows for complicated distributions to be approximated by simpler distributions.

Limit Theorems¶

Now that we have all of these notions of convergence, we can apply them to different situations and see what kinds of claims we can construct from them.

Weak Law of Large Numbers. Let $\lbrace X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_n \rbrace$ be an iid (independent, identically distributed) set of random variables with finite mean $\mathbb{E}(X_k)=\mu$ and finite variance. Let $\overline{X}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_k X_k$. Then, we have $\overline{X}_n \overset{P}{\to} \mu$. This result is important because we frequently estimate parameters using an averaging process of some kind. This basically justifies this in terms of convergence in probability. Informally, this means that the distribution of $\overline{X}_n$ becomes concentrated around $\mu$ as $n\rightarrow\infty$.

Strong Law of Large Numbers. Let $\lbrace X_1,X_2,\ldots,\rbrace$ be an iid set of random variables. Suppose that $\mu=\mathbb{E}\vert X_i\vert<\infty$, then $\overline{X}_n \overset{as}{\to} \mu$. The reason this is called the strong law is that it implies the weak law because almost sure convergence implies convergence in probability. The so- called Komogorov criterion gives the convergence of the following,

$$ \sum_k \frac{\sigma_k^2}{k^2} $$as a sufficient condition for concluding that the Strong Law applies to the sequence $ \lbrace X_k \rbrace$ with corresponding $\lbrace \sigma_k^2 \rbrace$. As an example, consider an infinite sequence of Bernoulli trials with $X_i=1$ if the $i^{th}$ trial is successful. Then $\overline{X}_n$ is the relative frequency of successes in $n$ trials and $\mathbb{E}(X_i)$ is the probability $p$ of success on the $i^{th}$ trial. With all that established, the Weak Law says only that if we consider a sufficiently large and fixed $n$, the probability that the relative frequency will converge to $p$ is guaranteed. The Strong Law states that if we regard the observation of all the infinite $\lbrace X_i \rbrace$ as one performance of the experiment, the relative frequency of successes will almost surely converge to $p$. The difference between the Strong Law and the Weak Law of large numbers is subtle and rarely arises in practical applications of probability theory.

Central Limit Theorem. Although the Weak Law of Large Numbers tells us that the distribution of $\overline{X}_n$ becomes concentrated around $\mu$, it does not tell us what that distribution is. The Central Limit Theorem (CLT) says that $\overline{X}_n$ has a distribution that is approximately Normal with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2/n$. Amazingly, nothing is assumed about the distribution of $X_i$, except the existence of the mean and variance. The following is the Central Limit Theorem: Let $\lbrace X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_n \rbrace$ be iid with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$. Then,

$$ Z_n = \frac{\sqrt{n}(\overline{X}_n-\mu)}{\sigma} \overset{P}{\longrightarrow} Z\sim\mathcal{N}(0,1) $$The loose interpretation of the Central Limit Theorem is that $\overline{X}_n$ can be legitimately approximated by a Normal distribution. Because we are talking about convergence in probability here, claims about probability are legitimized, not claims about the random variable itself. Intuitively, this shows that normality arises from sums of small, independent disturbances of finite variance. Technically, the finite variance assumption is essential for normality. Although the Central Limit Theorem provides a powerful, general approximation, the quality of the approximation for a particular situation still depends on the original (usually unknown) distribution.